Share

CRAZY SEXY COOL

In 1957, artist Richard Hamilton wrote a letter to friends Allison & Peter Smithson that would become the accidental declaration of a movement:

‘Pop Art is: Popular (designed for a mass audience), Transient (short-term solution), Expendable (easily forgotten), Low cost, Mass produced, Young (aimed at youth), Witty, Sexy, Gimmicky, Glamorous, Big Business.’

Forty years later, the hyperactive high-speed mania of 1997’s media landscape makes this pronouncement read like it could be said about practically any modern art form. Zooming up to the fast approaching millennium, media consumption as a past time – and as an industry – was booming and expanding at breakneck speeds. At home video game consoles, formerly too niche or too expensive for mass market appeal, rapidly found their stake with a more commercial audience with the release of the more accessible 5th generation of consoles.

Years of churning growth and expansion into wider markets meant that, in the late 1990’s, games as a medium could suddenly be sexy, gimmicky, sometimes glamorous, and often big business.

Ulala’s Swingin’ Report Show

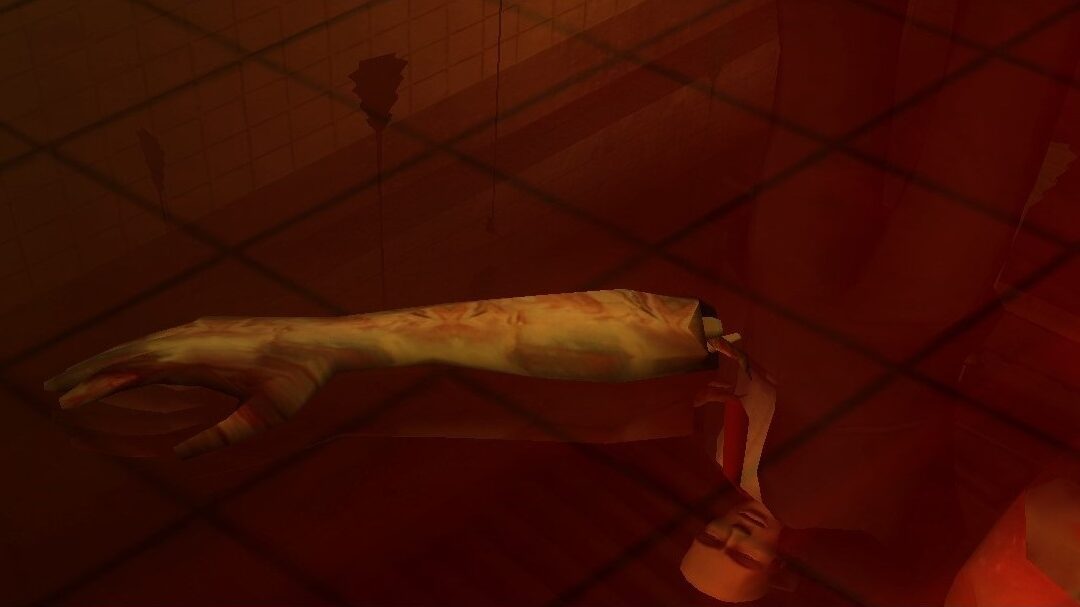

1999 saw the Japanese release of a new aesthetic giant in the Sega stable: Space Channel 5. The game has a paper thin premise which it makes up for in spades with its ambitious vision: You play as Ulala, a twenty-something reporter for the titular Space Channel 5, whose scoop of the hour is to investigate an invasion of dancing aliens wrecking havoc on spaceports and luxury liners by, well, dancing. These aliens, expressionless and bearing more than a passing resemblance to Among Us characters, hypnotize WASP-y space divas and gangly school children with ray guns as part of some greater machination that, you guessed it, involves the fate of the galaxy.

Developed by Tetsuya Mizuguchi, the birth of Space Channel 5 came from a request from Sega for a game that appealed specifically to the oft-ignored base of casual female gamers. “This was the first I’d heard of casual female gamers”, Mizuguchi said, “so I didn’t really know what to do. I personally interviewed a lot of young girls, trying to find out what they like.”

The result was a game more puzzle focused and less competitive, not to mention more visual. Space Channel 5 is all bright colors, 3D .mov backgrounds, and saccharine swinging 60’s. Ulala sways and pouts in a latex mini dress and go go boots, floppy neon aliens croon, chrome discs spin through the air, and NPC’s strut behind you in bubble wrap space suits. With an uncomplicated story and control system, Space Channel 5 is all flashing lights and mass market popcorn, and its kernel substance lies only in how unabashedly fun it is.

The Politics of Pretty

Meanwhile, the same year as Space Channel 5’s US release, Japanese pop art powerhouse Takashi Murakami was prepping his Superflat theory for publication. The theory points to Japan’s legacy of flirting with flattened 2-dimensional imagery, and posits that contemporary “flattened” art involves not necessarily a visual flattening, but a reduction of the difference between high and low art. The consumerism, sexual fetishism, and shallow emptiness of contemporary otaku culture are slyly referenced with pieces that visually read as hyper-kawaii, saccharine, and manic.

Murakami was taking fluff and turning into social commentary. Meanwhile, simplistic but visually frenzied rhythm games like Space Channel 5, PaRappa the Rapper, and Jet Set Radio were taking the visual components of commentary and turning them back into fluff. It was a beautiful machine, both sides churning profits for creators, and fodder for both the highbrow and the unpretentious.

Murakami’s pop art practice of creating high art out of “low” art was elevated to the next level by further repackaging his own “high art” pieces into a slew of affordable merchandise; Pillows and t-shirts of his grinning flowers can be found in almost any Japanese trinket store even today. While Space Channel 5 may not draw the same crowd to its titles anymore, you’d be hard pressed to find a gamer who hasn’t run across an Ulala figurine or neon poster of its characters and been drawn to the spangly, sparkly visuals.

The gimmicky, mass produced business of pop art thrived in the rhythm titles of the late 90’s and early 2000’s, maybe because artists like Murakami brought the aesthetic back into the Japanese zeitgeist, but maybe also because creators were rejecting video games as just a mass market medium. By making their rhythm titles an easily digestible creators were not only encouraging the wider appeal that was thriving in the late 90’s, but also making a statement about there still being intrinsic value in games as an art form, in spite of – or maybe irregardless of – that consumeristic appeal.

Pop art’s goal as a whole was to create high art from the everyday, but regardless of Murakami’s more cynical approach it was also to draw attention to the art & beauty already intrinsic in cultural objects rejected as déclassé. The movement inspired a closer look at mediums that were hastily rejected from the sweeping eye of fine art criticism, like comic books and advertising, and with video games still finding their place in the art world – and the market – the pop art movement in the late 1990’s was a stark examination of these growing pains. Games have grown so much in the 20 years since this movement took hold, but this idea of whether they can be “high art” or art at all is still raging on today. While the late 90’s didn’t settle the score, they did at least leave us with a legacy of something to think about, and something beautiful to look at while we’re at it.