Share

Fatal Frame has always deserved better than it got.

The first time I heard of it, it sounded ridiculous, like something between a theme-park ride and Pokemon Snap. In Fatal Frame—also known as Zero in Japan and Project Zero in Europe—you defend yourself against hostile ghosts by taking pictures of them with an antique camera.

It doesn’t sound like it ought to be a horrifying experience, but it absolutely is. The first three Fatal Frames, which make up an uneven but complete story, are easily some of the scariest games of their console generation. They take cues from Japanese horror, Resident Evil (resource scarcity), and Silent Hill (phenomenal sound design and use of darkness to build atmosphere), and wrap them up in a challenging, violent haunted-house photo safari.

Unfortunately, they never managed to be more than cult classics. Fatal Frame as a franchise isn’t exactly forgotten—it’s got a couple of trophies in Super Smash Bros. Ultimate, if nothing else—but it’s largely neglected. A lot of horror fans, like me, will wax poetic about Fatal Frame if you give them any chance at all, but that never translated into retail success.

This week marks a Hail Mary for Fatal Frame, as its publisher Koei Tecmo is rereleasing the latest, currently last, and worst-reviewed game in the series, 2014’s Maiden of Black Water. It’s a good move for game preservationists, as Black Water is one of the last Wii-U exclusives to get ported off the system, but it’s not likely to give the franchise the bump it needs.

It is, however, a good time to look back at one of the great, dead franchises of survival horror. Fatal Frame should’ve been a success story, but through mismanagement, mistakes, and pure bad luck, it’s become a genre footnote.

The Tale of the Tape

To Koei Tecmo’s credit, it’s stuck with Fatal Frame for a lot longer than it arguably should’ve. Fatal Frame, to my surprise, has consistently been one of the lowest-selling series in its publisher’s lineup. According to a 2014 report by Famitsu, all five core games in the Fatal Frame series only sold 1.2 million units total between 2001 and 2014.

The best-selling game in the core series, 2008’s Mask of the Lunar Eclipse, is a Japanese Wii exclusive that only moved 75,000 copies. Every other game in the franchise has struggled to crack the 60,000 mark.

Trying to figure out why Fatal Frame bombed so hard is down to reading tea leaves. Its creator, Makoto Shibata, has half-seriously suggested in interviews that the original Fatal Frame in particular might have been too scary for its own good. Both fans and journalists have told Shibata that they simply weren’t able to finish it.

There might be something to that. It’s easy to forget that the sixth generation of consoles was a virtual killing floor for a lot of games with niche appeal, and horror is an innately niche genre from the jump. A lot of creepy games came and went in the 2000s without making a splash (shout-out to Echo Night and Cold Fear), and Fatal Frame would fit neatly at the top of that list.

It’s also unique among the big Japanese survival horror franchises for actually being set in Japan, and drawing on Japanese mythology and folklore for its story, as opposed to the Western-set cinematic beerslams of a Resident Evil or Silent Hill. That would naturally limit Fatal Frame‘s international appeal, particularly since it also doesn’t offer the built-in catharsis of shotgunning monsters in half.

As such, Fatal Frame ended up occupying a niche within a niche within a niche. In 2021, where digital storefronts reward, or at least don’t punish, games for being weird, Fatal Frame might’ve had more luck. In 2001, however, it was working with a substantial handicap.

The question, then, isn’t why Koei Tecmo doesn’t support Fatal Frame, but why it stuck with Fatal Frame for as long as it did. Its reviews and word of mouth have always been positive, so maybe Koei Tecmo was hoping it would suddenly boil over one day, but it never did.

Ghosts of a Chance

That isn’t helped by how hard it is to actually play Fatal Frame in 2021. The easiest legal way to find any of the first three games in North America is to find a working PlayStation 3 and buy them as PS2 Classics for $9.99 each. The fourth is, as noted above, a Japanese Wii exclusive, although a fan translation exists.

At time of writing, neither of the first two Fatal Frames have been added to the Xbox backwards compatibility program, and Sony’s current disinterest in historical preservation means you can’t even see the PS2 Classics rereleases on the PS4/5 version of the PlayStation Network. Fatal Frame, at this point, is a ghost story in its own right.

In a perfect world, Koei Tecmo could assemble the first three games in a collection and sell it digitally, for the sake of preservation if nothing else. This is, to be fair, currently on the table.

If it’s depending on Maiden of Black Water to reignite interest in the series, though, it’s like trying to sell somebody on the merits of the Indiana Jones series by showing them Kingdom of the Crystal Skull. It feels like it’s meant as a well-disguised mercy kill.

Haunting Ground

It might also be an exorcism. One of the peculiar behind-the-scenes details of Fatal Frame is that the people who have worked on it all ended up with ghost stories of their own.

The original inspiration for the series came from Makoto Shibata’s childhood, dating back to a haunted country road that he lived next to as a kid. When his father gave him an old, broken camera, it sparked the idea that ended up becoming Fatal Frame.

Over the course of the first three games’ development, various employees on its development team reported a procession of peculiar incidents, both in their homes and at the Tecmo offices. This included copies of the game that seemed to shake or vibrate on their own, glass randomly shattering, phantom knocks on doors, and ghostly footsteps. Shibata himself reported an incident of a ghost seemingly infiltrating his brand-new apartment.

It’s another mark in Koei Tecmo’s favor, in a weird sort of way, that Fatal Frame continued at all after the third game. Not only did they not sell well, but to hear them tell it, there was some peculiar bleed-through between the games’ events and the developers’ lives.

2001: Fatal Frame

In 1986 Japan, Miku Hinasaki comes to the famously haunted Himuro Mansion in search of her brother. Mafuyu disappeared while looking for his equally-disappeared mentor, the novelist Junsei Takamine.

Both Miku and Mafuyu have inherited the ability to see ghosts from their mother, which is part of what lets Miku survive at all. The rest is down to Mafuyu’s old camera, which affects the ghosts of Himuro Mansion like a weapon. When Miku takes a picture of a ghost with the camera, it has the possibility to destroy them. That sets Miku up to pursue Mafuyu deeper into the mansion’s grounds, where she discovers the reasons why the mansion is haunted in the first place.

The original Fatal Frame is the most difficult of the lot, as it leans heavily on resource scarcity. If you simply snapshot your way through the game, you’ll end up out of film two-thirds in. Instead, you’re supposed to carefully wait and time your shots, choosing the most perfect moment for a photo, in a mechanic that gives the series its American name.

Fatal Frame also features multiple endings. The “Special Edition” port for the Xbox even includes a “golden” ending, where everything works out for Miku about as well as could be expected. Naturally, that isn’t the one that ended up being canon, as established by Fatal Frame III.

2003: Crimson Butterfly

In 1988, a strange butterfly lures Mayu Amakura into the woods. When her twin sister and protector Mio chases her, they both end up in the abandoned Minakami Village, which is haunted by ghosts of its own.

Minakami is the site of an old ritual, the Crimson Sacrifice, where one twin ritually sacrifices the other, in order to keep a lid on a gateway to darkness called the Hellish Abyss.

Generations ago, Yae and Sae Kurosawa tried to escape from the village before they were forced to complete the ritual. Yae got away, but Sae and the rest of the village died in the catastrophe that the ritual was meant to prevent.

Now, Minakami Village is trapped in a time loop, where its ghosts, including Sae, constantly relive the night before the failed Crimson Sacrifice. The only way to break the loop is to draw another set of twins into the village and finish the ritual. Mio, armed with a Camera Obscura, must find Mayu before it’s too late.

It’s All Downhill from Here

Crimson Butterfly is the best-reviewed game in the series, and with good reason. It’s much more cohesive than the games that came afterward, with a solid central hook. It does dial back the challenge from the original Fatal Frame, most notably in that you actually have a fallback weapon.

The weakest type of film for your camera in Crimson Butterfly also features unlimited exposures, which means you can’t run out of “ammo.” That takes away some of the first game’s razor’s-edge feeling, which was a deliberate decision by the developers.

That doesn’t mean it’s not scary. If you were going to sit down and make a list of the best straight-up horror games of the PS2/Xbox/GameCube era, Crimson Butterfly easily makes the top 10, and would have a realistic shot at #1 in a universe where Silent Hill 2 didn’t exist.

Fun fact: there aren’t many threads that join Crimson Butterfly with the original Fatal Frame, but one of them is that the first game establishes what happened to Yae Kurosawa after she escaped from Minakami. Her ghost can be found and fought by Miku in the Himuro Mansion. Her granddaughter Miyuki is Miku and Mafuyu’s mother.

2005: The Tormented

A few months after the events of Crimson Butterfly, three characters each end up having the same recurring nightmare, in which they each come to and explore the “Manor of Sleep.”

Rei Kurosawa is a photographer haunted by the recent death of her fiancé. Miku Hinasaki is still mourning her brother Mafuyu. Kei Amakura is close with his niece Mio. All three of them are seeing the same apparition of a tattooed ghost, and seem to have fallen under the same curse, triggered by survivor’s guilt. The only solution they can find for it is waiting for them somewhere inside the Manor of Sleep.

You can also draw a pretty straight line between Fatal Frame III and the relatively contemporaneous Silent Hill 4; both games go out of their way to establish the player character’s home as a safe place, only to make it that much worse when it suddenly isn’t.

Fatal Frame III is the only game in the original trilogy that didn’t get an enhanced Xbox port. It’s weaker than the previous two games, but has its moments, and it’s structured like a send-off. If it had been the last Fatal Frame, it would function as a decent if loose closing chapter for the series.

2008: Mask of the Lunar Eclipse

On paper, Fatal Frame was a natural fit for the Wii. The Wiimote works well with various light-gun shooters like House of the Dead, and the same controls effectively translate to Fatal Frame’s Camera Obscura.

Mask of the Lunar Eclipse was developed by the famously quirky Japanese studio Grasshopper Manufacture, with good ol’ SUDA51 (Killer7, No More Heroes) co-directing it with Makoto Shibata.

Mask is actually the best-selling single release in Fatal Frame history, but again, that isn’t saying much; its Japanese sales were still low enough that Nintendo canceled Mask’s European and American releases. A fan patch eventually translated Mask for English-speaking audiences, but you have to soft-mod your Wii to play it.

Its plot has little to do with the rest of the series, aside from the appearance of a Camera Obscura. In 1970, five girls are kidnapped and brought to the island of Rogetsu by a would-be serial killer. A detective, Choshiro Kirishima, rescues all five, but they’ve lost their memories.

Ten years later, after the mysterious deaths of two of the abductees, Ruka Minazuki ignores her mother’s warning and returns to the now-abandoned island in search of answers. Once again, that means running headlong into a warren of angry ghosts, but once again, there’s a handy Camera Obscura that Ruka can use to defend herself.

2014: Fatal Frame: Maiden of Black Water

Makoto Shibata returned as director for Maiden of Black Water, which was co-developed by Koei Tecmo and Nintendo’s Software Planning & Development Division. The inspiration for the game came from the Wii-U’s unique controls, where a player could use the screen built into the Wii-U’s gamepad as if it were the Camera Obscura.

Once again, players are tossed into a part of Japan where evil has historically been kept at bay by regular human sacrifices. This time, it’s Mt. Hikami, which has become haunted by the spirits of the maidens that once tended its shrines.

In the modern day, Hikami is a popular site for disappearances and suicides. That leads antique shop owner Yuri Kozukata (who you may recognize as an assist trophy) and her friend Ren Hojo to the mountain, in search of a missing girl. At the same time, Miu Hinasaki heads to Hikami in search of her mother Miku, the heroine of the original Fatal Frame, who abandoned Miu at birth.

Failure to Reboot

On paper, Maiden of Black Water is a return to type for Fatal Frame, and is a clear set-up to continue the overall franchise. Most notably, it clarifies the history of the Camera Obscura; while the original trilogy made it seem like it was a one-of-a-kind item, Maiden retcons each Camera in the series as a different prototype created by the late occultist Dr. Kunihiko Asou.

What slows it down, however, are some truly bizarre storytelling decisions. I’m going to avoid spoilers, but it’s enough to say that the Wii-U version of Maiden has some of the most divisive reviews of any Fatal Frame. Somehow, the game that SUDA51 wasn’t involved with is also the one that’s made the weirdest choices.

The least spoilery issue of the lot is that Maiden is easily the most fanservice-y entry in the core Fatal Frame series. It uses graphics tech from Koei Tecmo’s Dead or Alive 5 to make characters look realistically wet, which is both a gameplay mechanic—wet characters inflict more damage with shots from the Camera Obscura, but ghosts can inflict a status ailment that can only be removed by drying off—and an excuse to make Yuri and Miu look sexily disheveled. It’s very The 3rd Birthday, and is why Black Water has a higher CERO rating in Japan than any other game in the series.

The 2021 rerelease of Black Water is a remaster that adds a few new features, such as alternate costumes for the main cast and new settings for the Camera Obscura. It doesn’t feature any rewrites, however, so it’s likely going to be a weird week on Horror Games Twitter. I look forward to a new generation of players reporting back on the mad craziness of Black Water‘s endings.

In retrospect, there’s a lot to compare here between the dire state of the latter half of the Silent Hill series and how Fatal Frame ended up sputtering to a halt. Neither franchise quite knew what to do with itself after the third entry, and in both cases, the developers tried to take the games in strange, theoretically mainstream-friendly directions.

Dead or Alive or Just Dead

In a particularly weird crossover, there’s an unlockable bonus scenario in Black Water where players take the role of Ayane, one of the primary characters in Koei Tecmo’s Dead or Alive series. She was reportedly brought in, with Nintendo’s encouragement, to expand the game’s potential fanbase.

Ayane is hired to find a girl who’s gone missing in the vicinity of Mt. Hikami. With her typical ninja weaponry proving useless against the area’s ghosts, Ayane, like Kei in Fatal Frame III, has to rely on evasion and distraction to survive.

For those who like to keep track of this sort of thing, this means Fatal Frame is now set in the same universe as Dead or Alive and the 2000s-era Ninja Gaiden trilogy, which honestly isn’t that weird. Dead or Alive already has a couple of mythical monsters, a bunch of cloning, teleporting ninjas, and the alien life form known as Zack, so why wouldn’t it have angry haunted mansions?

That also gives Fatal Frame a connection to Virtua Fighter, King of Fighters, and eventually, through the special guest fighter in the Xbox version of Dead or Alive 4, Halo. That, in turn, opens the possibility for a future Fatal Frame that happens to co-star a SPARTAN-II, if not the Master Chief himself, which is just fun to think about.

Spin-Offs and Side Projects

While it doesn’t bear the Fatal Frame name or branding, the 2012 Nintendo 3DS game Spirit Camera is an augmented-reality take on the core Fatal Frame gameplay. It uses the 3DS’s outer cameras as a makeshift Camera Obscura, as the player is transported into a haunted house by accidentally interacting with a cursed book. With a sassy 54 rating on Metacritic, it’s only worth tracking down for the craziest of completionists.

There’s also a Hollywood adaptation of the original Fatal Frame that’s been in development hell for roughly 18 years now, but has never officially been canceled.

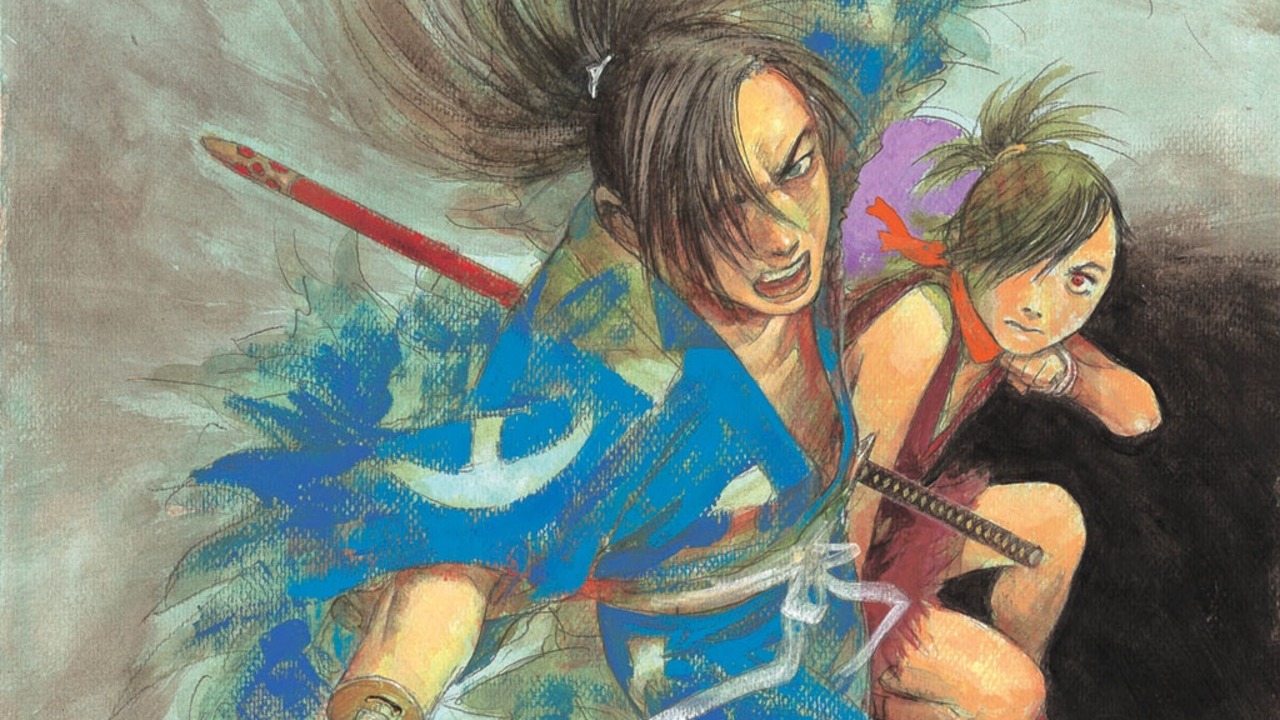

Japanese adaptations have been a little more successful, and several Fatal Frame novels and manga have been released over the years. In 2014, Eiji Otsuka adapted his Fatal Frame novel, A Curse Affecting Only Girls, into a live-action movie that was directed and co-written by Mari Asato.

There’s been a resurgence of horror as a genre in the last few years, thanks to film production houses like Blumhouse and the unexpected success of movies like the 2017 adaptation of Stephen King’s It. In video games, survival horror has come roaring back after the popularity of the 2019 remake of Resident Evil 2, with tons of new AAA projects on the horizon.

In theory, this is the right moment to try to get Fatal Frame the audience it’s always deserved. The problem is that Koei Tecmo is trying to pull it off with the least suitable game in the series for the job. Black Water could be enough of a spotlight to get the original Fatal Frames remastered for a more receptive modern audience, fingers crossed, but it could also end up burying the franchise once and for all.