Share

I’ve been playing a lot of No More Heroes III recently. I find this game genuinely fascinating due to the shakiness of its construction. While I’ve yet to finish the title, I think that I love it – in spite of the myriad issues that are both intrinsic to its design and related to its woeful technical fidelity. What makes these challenges so easy to overlook is the lavish style here that is characteristic of SUDA51’s entire body of work. I find it difficult to grumble at No More Heroes‘ repetitious mission structures when I’m riding in a tank shooting at alligators who are trying to invade a facsimile of Normandy’s beaches in an overt satire of grey-brown military shooters, as Travis Touchdown shouts “fuckhead!” all the while. This game is weird, dude.

That weirdness and commitment to style is precisely why No More Heroes III is quickly becoming one of my favorite 2021 releases. Simultaneously, this style is posing an interesting quandary. No More Heroes III has made me deliberately contemplate what we, as an industry and community, mean when we say that a modern game feels retro. Whether we’re calling a title retro-inspired, nostalgia-driven, a throwback, or any other like expressions, we spend a lot of time talking about how new games look back. But what do we mean when we say that? Are the games that we quantify as feeling retro actually retro in any sort of qualitative sense? Does this sentiment actually express anything at all?

These questions are vitally important when interpreting No More Heroes III. A huge part of SUDA’s style leans on motifs from 80s and 90s gaming culture, as well as pop culture from that time overall. I love the texture and personality that No More Heroes is afforded by these choices. After all, the player interprets the world through Travis’ nostalgic otaku eyes. While I have enjoyed that flavor in the context of this experience, it has helped clarify my issues with the larger modern connotation of stating that a game feels retro. See, SUDA leverages retro hallmarks – arcade leaderboards, CRT filtering, and text-adventure overlays being just three of the countless nods – as aesthetics. Rarely do these retro trappings amount to much on a design level. I’m not bothered by that inherently. SUDA’s intention is to evoke a bygone period which informs No More Heroes‘ world, not to build a mechanical homage to that time. If anything, I’d argue that Travis Strikes Again is far closer to the latter. However, the notion of retro being an aesthetic does open the door for me to explore the use of this term further. Because, for retro to mean something more genuine, I think that the concept of retro needs to fundamentally inform design.

Rethinking the definition of retro feel

So let’s think for a second about one of my favorite 2021 titles, Cyber Shadow. This game is rad. Effectively, it’s an action-platformer that draws heavily upon classics like Ninja Gaiden. And, save for a slow windup, I think that Cyber Shadow is damn near perfect. But is it genuinely a retro throwback as many consider it to be? Well, to answer that we need to think about fundamental design considerations. At that level, I see reason to believe that Cyber Shadow isn’t truly authentic. Most critically, I probably couldn’t be convinced that Cyber Shadow could run on actual NES hardware, despite its NES-era visual style. This is a key distinction. I believe that if we are to consider modern games as being part of a retro tradition, they should adopt that tradition from a technical and design perspective as well as a visual one.

Certain elements of Cyber Shadow do fit within the technical confines of the era, as Aarne Hunziker, the game’s developer, discussed in an interview with Nintendo Life. Yet, he also reveals that the game does push beyond what would’ve been possible on that 80s hardware. Techniques such as parallax scrolling are used here in ways that would’ve been impossible on NES but contribute to the title’s absolutely beautiful visuals. This is just one example of how Cyber Shadow, and myriad games like it, use visual styles that are predicated on capturing the broad strokes of the past without strictly adhering to the finest technical requirements of the time.

Let’s now think about Cyber Shadow mechanically. Does it sit within the confines of the 8-bit era it seeks to replicate? Well, kind of. In that same Nintendo Life interview, Hunziker cites the ability to render more sprites on screen than what the NES would’ve been legitimately capable of. Choices like this do undeniably sculpt an experience that, from a gameplay perspective, operates outside of what would’ve been possible before. Likewise, Cyber Shadow also benefits from decades of industry advancement and refinement. Hunziker is a great designer who implemented many interesting ideas such as a dynamic difficulty system, something that simply wouldn’t have been considered in the time of Ninja Gaiden. But, like its aesthetic, Cyber Shadow captures the broad strokes and high-level design principles of this past era very well. It’s a sharp and mechanically simple action platformer which does clearly evoke that 8-bit time, even though Cyber Shadow is demonstrably operating with modern affordances. However, I then have to wonder about whether it’s really accurate to say that the game feels that retro, all things considered.

I’m not saying that the game’s quality is negatively affected by not adhering to third-generation design principles and technology. If anything, I’m saying the opposite. The ways that Hunziker fudges technical limitations makes Cyber Shadow so much better than something like Ninja Gaiden. And I love Ninja Gaiden! But, it’s also buried under rusty, decades-old tropes and ideas. While its pixel art is impressive for the time (especially during cinematics), it’s lacking in detail and richness when compared to Cyber Shadow. The latter is how we rosily imagine the 8-bit aesthetic to be, whereas the former is how it actually is. This extends to the gameplay, which is satisfying in Ninja Gaiden but completely unrefined. Don’t get me started on enemy spawn points and level design – Ninja Gaiden totally fumbles in these respects. Games like Cyber Shadow sand down these rough edges partially by merit of stronger tech and partially by merit of further design experience.

As such, I have trouble with the classification of something like Cyber Shadow. Hunziker calls the game 8-bit+, which I can get behind. However, its general connotation in the larger industry is straight up retro – which it clearly isn’t. It’s evocative and evolutionary of that NES period, but it’s unable to fit nicely within the confines of what 8-bit actually is. The veneer of retro doesn’t equate to true retro design, I suppose. But, at least that veneer did inform the high-level conceits of the Cyber Shadow experience, whereas retro trappings are only overlaid upon No More Heroes III’s foundations.

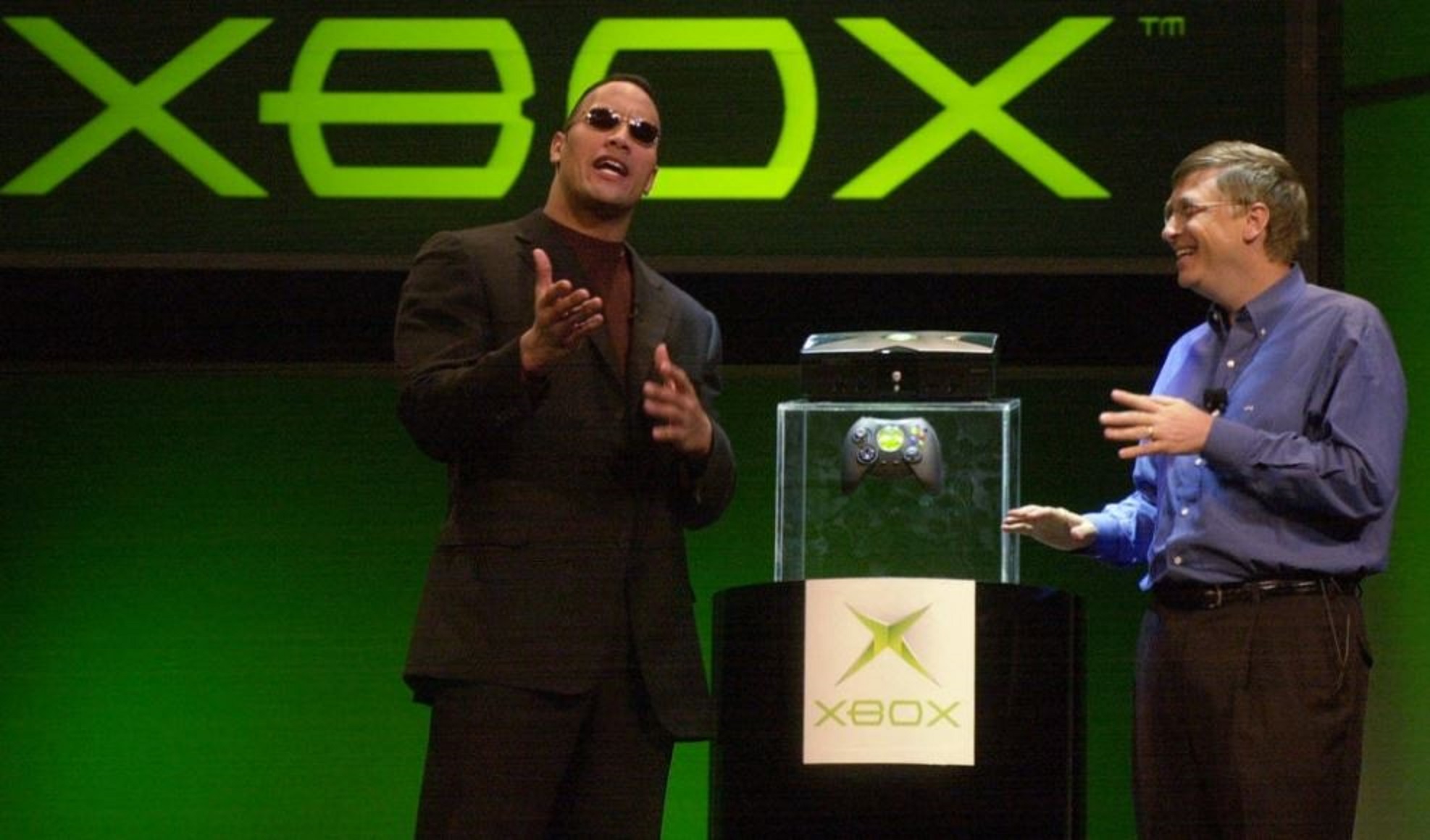

it doesn’t get much more retro than this

Using classical limitations to define the core of your design in order really feel retro may seem like a high bar, but it’s a truly important one to clear. Otherwise, you’re not really building an experience which feels old-school. Think about the many examples of new Hollywood movies that add film grain to digital footage in postproduction to simulate an old Hollywood feel. There’s nothing inherently special or authentic about that. It misses the point of shooting on actual film and fails to truly capture the production conditions of a past era. Shooting with film and shooting with a digital camera are markedly different experiences. Production conditions matter in cinema, and they matter in games. They inform the final product. If the goal is to return the audience to a former time, then authenticity is essential, and authenticity starts with genuine adherence to older techniques and specifications.

Still, given the existence of digital film grain in cinema or simulated retro elements in gaming, there is clearly a continuity to the idea of evoking retro works. So, if we’re starting to build that continuity, we’re establishing something that runs the gamut from retro as a design philosophy to retro as an aesthetic. I’d say that Cyber Shadow is somewhat of a midpoint between those identities whereas No More Heroes is clearly far to the right. There are games that squarely operate on the left hand side of that continuity, although they rarely get much attention. One of my favorites is Tanglewood. It’s a brilliant little mascot platformer that was developed completely within the confines of Sega Genesis hardware, written within 68000 assembly language.

Stem to stern, this is a game that was developed during the modern era but within a simulated 90s context. It’s incredibly unique, and if you want to know more about Tanglewood, I got to interview its designer and programmer, Matt Phillips, back in 2018. We talked about the challenges of this authentic development process, and how he still managed to apply modern design philosophies to a rigidly old-school project without compromising this commitment to Genesis hardware. While I feel cripplingly self-indulgent by linking to my own interview here, it’s relevant to the discussion and truly fascinating! Not enough people talk about Tanglewood.

This is just one of many games that distinguish themselves from their pseudo-retro peers by working within the conditions of older hardware. Many of these titles even get limited physical releases on the older hardware that they’re build within! The Dreamcast frequently receives new titles because of this dedicated homebrew development community. I’ve spent a lot of time watching YouTubers like Adam Koralik unbox and discuss indie games that are built on Dreamcast hardware and then pressed to discs. Of course, these games usually launch on digital storefronts too. But the fact that they can run on this older tech makes it very easy to quantify them as feeling retro.

the importance of being precise

Bearing titles like this in mind, I think we can establish a pretty full continuity from Tanglewood to No More Heroes. And yes, I recognize that these two games probably have never been brought into conversation before, and probably never will be again. But it’s important to do so! One represents retro as a total design identity, and the other represents retro as an aesthetic primarily. But the reason that I spent so much time on Cyber Shadow is that the lane it travels along is where most of its peers are situated. They may be visually and mechanically evocative of an older time, but neither their presentation or gameplay truly capture the limitations of their respective era. As such, I think we need more terms to differentiate these different uses of retro elements.

While this may sound gatekeep-y, it isn’t meant that way. Instead it comes from a place of wanting to better define terms. I’ve been thinking about this a lot recently, especially as my Junior year of college gets underway. I’m an English and Film Studies double major, so I spend a lot of time thinking critically about various art forms and their production. Part of my ability to do that can be attributed to clearly defined lexicons of terms used to discuss cinema and prose with. Gaming doesn’t have that. I want gaming to be legitimized through the lens of higher education as the rich cultural study that it can and should be. However, a lot about this industry will need to be overhauled for that to be possible. Part of that will entail developing a precision in the terms that we use.

Obviously this is a much bigger issue than just one term, and arguably I may not be going far enough here. Some may rightfully claim that we shouldn’t be calling any modern games retro in any respect, regardless of the framework that they’re built within. I think that’s fair too. And I think that I may have constructed this hypothetical person to acknowledge their perspective without having to assert it myself. Oh well. The high level point is that our industry speaks about games with a vernacular that’s too amorphous, and No More Heroes III made me reckon with that.

Don’t even get me started on search action.